Of course, there are many different perspectives of this topic with those who debate morality is always objective, objective only in certain contexts, or entirely subjective. Most religions today support and firmly teach the first two, although it appears that our popular culture prefers the latter. Let’s examine why and see if we can answer this question together. After careful reflection of what I’ve touched-on here as well as some additional research I encourage you to do on your own.

First, let’s start with a brief philosophical overview of different approaches toward ethics:

Plato – Focus on the struggle of morality

In The Republic, Plato basically argues why one should strive to be moral. He believes that morality is true justice, not in the sense of just doing the right thing, but more importantly, as a defense of one’s innermost character. He presents his argument in a form of dialogue between two characters, Socrates, a wise man and defender of authentic morality, and Glaucon, who represents the views of society/the majority. Glaucon argues that the unjust/immoral life the best life, and that those who choose to perform moral deeds only do so out of obligation (fear of punishment or for self-interest) or to maintain a reputation, not just for the sake of doing good. He supports this argument through a hypothetical instance of someone having a ring of invisibility, that he would not perform true good if nobody was watching, for there would be no fear of consequence. He also claims that living an unjust life is obviously better, filled with money, friends, and reputation, while those who seek justice are miserable and suffering, at the bottom of the social latter.

Plato uses Socrates, whose character was indeed based on his former mentor, on the other hand, to argue that those who truly recognize what justice is are held to a higher expectation: to seek good for its own sake and the sake of the results. A just life is noble, simple, and the inner-reality bears authentic happiness as opposed to mere illusions/appearances of it. He claims that one can test if another is truly just by getting the majority to view him as “a disgrace,” and if he is not affected by infamy or any negative consequences, his soul is justly-ordered. He believed that we learn how to live this life through discussion and intellect. The Republic, as a result, is an argument in and of itself for why one should strive to be moral in such a world where appearances at first glance seem more enticing than true justice.

Aristotle – Focus on the Human Good

Aristotle

Aristotle was Plato’s student and greatest critic. He thought it was more important to focus on good itself, and not necessarily the inner-most struggle of morality. He believed in practical ethics, and that we learn how to live a good life by practicing good, not just through intellect as Plato focused on. To Aristotle, human good is a result of rationality in accordance with excellence (doing what one is supposed to do and doing it well). One’s feelings and actions must also be in sync, as there should not be any psychological turmoil between what you want to do and what you actually do in a good person who performs good actions. Aristotle also believed in moral luck, or the idea that the environment in which you were raised can either provide or fail you the opportunities to become good.

Spinoza – Focus on Alignment with the cosmos and overcoming passions

Spinoza

Spinoza was one of the first excommunicated Jews because of his pantheistic views of God being one with the universe or cosmos rather than an independent divine being that intervenes with the physical world. He believed that true happiness comes from aligning oneself with nature/the cosmos/the universe, and that there was a necessary order with very set laws that a good man must adhere to. He viewed passions or emotions as outside of one’s control, forcing the unwise to make irrational judgements and engage in risky behaviors, whereas the wise were able to overcome these passions and have full control over their lives.

Hume – Focus on innate good and feelings

Hume was in direct contrast to Spinoza’s view on “uncontrollable” feelings. He believed that people are inherently good, and morality should be founded by the natural feelings within us, disagreeing with Aristotle’s notion of moral luck as well. Morality is within the power of the individual. Hume evaluated moral actions as those that were useful and came from human nature’s good will, whereas immoral actions were a result of education or poor social conditioning.

Kant – Focus on duty and moral law

Kant believed that only actions done out of duty have moral worth. He believed in an unconditioned duty innate in all human beings: we have the responsibility to do what we are supposed to do because it is right and for no other motive. Duty, however, can be constrained by guilt or fear. He believed that as rationale beings, we should treat one another with the same respect as ourselves. He was not concerned with sentiments like Hume; in fact, he believed feelings had nothing to do with morality. Kant distinguished between good and moral actions. Actions done from duty were considered moral as long as they followed certain principles, whereas actions that were not from duty could still be considered good but not moral. He was similar to Plato in that morality is justice in a sense that it is good for its own sake. He was similar to Spinoza in believing in some higher form of a universal law that guides human behavior as rationale beings.

Mill – Utilitarianism

Mill is nearly in direct contrast with Kant. Although, he was similar in that he disregarded feelings when it came to ethics. He was more of a consequentialist, believing that morality was not about any form of intrinsic worth but rather about the results it produces or intends to produce. Mill’s Greatest Happiness Principle was to maximize pleasure and minimize pain, and education was essential in overcoming any barrier toward happiness. He was egalitarian, believing that all lives were equal. In any decision involving morality, Mill would always argue that saving the most lives or losing the least lives is the most moral decision.

Nietzche – Morality is a Man-Made Construct

Nietzche

Nietzche took a very historical approach when describing ethics. He believed that morality is not a given because it has a clear origin. He believed that truths were different at different times throughout history, and that both ethics and morals go through phases/are not universal. Morals were more like “chapters” in the social values visible in respective time periods. There was a time before Judeo-Christian values, where there was no guilt, and he believed there would be a time in the future where this value system (or lack-of) will return. His most famous work was On the Genealogy of Morality, in which he divided human history into 3 periods:

- Past (Pre-Moral)

- Present (Moral)

- Future (Extra/Post-Moral)

Nietzche argued that in the past, before Jesus or rabbis, the value system used was functional and not moral. What was considered good was good because it was useful, such as being successful and surviving, and what was considered bad was bad because it was not-useful, such as being poor or weak. He argued that Judo-Christianity created a transvaluation, switching the society’s value systems from functionality, focused on survival to morality, focused on laws and virtues. As a result, the present is focused on one’s inner-life, intentions, and the role of the individual. Although to Nietzche, any form of self-sacrifice or morals are only signs of weakness, crippling human beings of their full potentials. He believed that in the future, human beings would reach a post-moral era of enlightenment in which people are no longer crippled by their inner lives. He viewed this era as moving beyond the past, realizing its flaws and the constraints of morality, and with humanity living life in its natural state as opposed to having some sort of imposed value-system. Nietzche viewed Kant’s sense of duty as constraining and his own view of a post-moral era as liberating.

I’d like to formally attribute popular culture’s and agnosticism’s view of religion today to Nietzche’s influence on ethical philosophy.

Nietzche, thank you for making a logical historical argument as to how morals are constructed and for causing many people to question any form of faith. You’ve played a vital role in making the world a more speculative place, but in some sense, acknowledging this weakness from an outsider’s perspective of morality was critical because it addressed some of the problems in the early Church as well as some “conversions” today. For example, a great number of those who “converted” in the early 4th century did so as a result of mass-conversion because a king or ruler had made the decision for them, as many youth experience when they go through the motions of religious practice today in order to not disappoint their parents. Religion went from being something freely practiced out of the love of God during times of persecution to more of an “expectation” that was not truly understood or embraced. People also were focusing on the strict rules as a means of avoiding eternal damnation instead of truly experiencing the liberating joy of faith and love. Nietzche recognized that religion in its misunderstood sense was constricting, rather than liberating. Although the Church today has always taught that religion should be practiced freely because it is liberating and not out of fear, more and more individuals today have not really grasped this concept. And, as a result, there are a lot of critics today of the hypocrisy of religion and these particular individuals. Nietzche’s speculation has helped bring searching individuals to greater truth of the beauty of religion, encouraging them to truly embrace their beliefs as opposed to living them out of fear or expectation.

Subjective Morality

Subjective morality is based upon the idea that an individual or group can determine what is right or wrong based upon their own interpretations. Subjective moralists, such as Nietzche and Hume would consider religion as being rooted in subjective reality because values’ origins cannot be proven. Because various religions have their own interpretations of right/wrong or good/evil, or include their own exceptions for these “rules,” they have to be considered subjective. For example, whether actions are important for salvation, whether pastors can marry, etc. are all beliefs that differ amongst different practices. This belief system can also be known as Cultural Relativism.

Relative Morality

Moral relativists believe that context is very important. Certain ideas can be considered true or false depending on the particular issue or standpoint. Similarly, certain actions can be considered good or bad depending on a situation. For example, killing someone is bad if it is an innocent person, but it is good if the person is a criminal like Hitler. It also depends on the person. What is right for someone can be “right” for them, but the same thing may be “bad” for someone else. This view typically is found outside of the realm of religion, or even more so in the realm of separation between Church and State. I think the best example can be found from those who consider themselves “personally” pro-life but “politically” pro-choice because although they think killing a baby in-utero is wrong, they think that they do not have the right to tell someone else what to do with their body. They believe it is murder, but they do not believe in

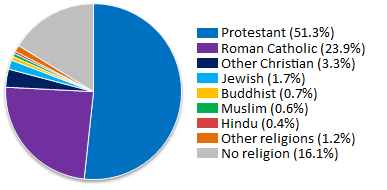

The irony of moral relativism is that most things that are hot-topics in the United States (abortion, pre-marital sex, gay marriage, euthanasia, etc.) are almost always considered “immoral” in nearly every religion. With over 80% of the population considering themselves to be “religious,” the vast majority of its culture appears to still advocate for each of these things as “rights,” despite their opposing religions.

Arguments against relativism:

Objective Morality

Objective morality is rooted in the idea of a universal law, similar to the beliefs of Kant, Plato, and Spinoza. Objective moralists believe that there is a particular human “code” helping us to determine what is right or what is wrong, and the existence of guilt or distress is evidence of the existence of a moral conscience, guiding one to discern between good and bad. Objective moralists believe that our human laws should mirror these universal laws. For example, the U.S. Declaration of Independence defines that all human beings should have the inalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. While relativists argue that this would mean people can do whatever they want to make themselves happy, objective moralists argue that there is a clear distinction to be made between good/evil or right/wrong. Popular objective moralists can be found within Islam, Judaism, and Christianity. Now, objective morality is not always black and white. It allows for some grey areas because morality can consider things such as intentions or justifications. For example, killing any human life in Judaism is objectively wrong; abortion is objectively immoral, but in the case when a mother’s life is at stake and all else has been tried to the best of the doctor’s and family’s ability, an abortion can be justified.

The Conscience

In Judaism, the Yetzer Ha-Tov fulfills the role of “conscience,” determining whether something is of a good or of a more animalistic instinct. In Islam, there exists a similar notion within human nature, although this ability is not natural, it is divine. In Christianity, it is truly called a “conscience“:

“In the depths of his conscience, man detects a law which he does not impose upon himself, but which holds him to obedience. Always summoning him to love and avoid evil, the voice of conscience can, when necessary, speak to his heart more specifically: do this, shun that. For man in his heart a law written by God. To obey it is the very dignity of man; according to it he will be judged.”

Second Vatican Council

Christianity recognizes the existence of objective norms, and as a result, one’s conscience can be skewed about divine law through one’s environment. For example, one can be conditioned to believe killing is morally permissible. It teaches that one’s conscience can be ill-formed as a result of poor moral upbringing. Conscience is a gift that must be disciplined and trained, and through habitual sin, one’s inner conscience can become distorted or even silenced (similar to the psychological notion of habituation or conditioning). The creation of a good moral conscience requires a great moral effort.

You don’t need religion to argue that morality is objective…?

Now, here’s where I’ll really get into the root of my argument. You don’t need to believe in God to practice virtue, or any form of natural law. In one example, you don’t have to be religious to believe that murder is wrong, and by murder, I mean the intentional killing of another human being. Why is this, though? Whether it’s because we are entitled to dignity as human persons (sound familiar?), or because as human beings we are incredible empathetic and self-aware and expect one another to be the same, it really doesn’t matter why it’s wrong. Most people in the world simply agree from a humanistic perspective. Although, when put in different contexts–for example as “mercy-killings” of infants (infanticide and abortion), of the elderly or sick (euthanasia)—–people tend to change their opinions or try to justify the intentional killing of another human being, though it remains murder as far as the broader definition is concerned.

I think the best example that can be examined regards the unlikely event that a contracted-surrogate mother decides that she no longer wishes to have the child and would like an abortion. According to moral relativism, this is permissible. It is her body, and it is her choice what to do with it. The mother who needed a surrogate has no right to intervene with another woman’s body, even if the baby is made-up of her DNA. Now, I’m sure it’s somewhere in the surrogate mother’s contract that she wouldn’t be allowed by law to do this or have an abortion, but let’s just say she went to an anonymous clinic that didn’t need to ask any personal questions to perform the procedure. I think most people’s immediate reactions would be that this is not okay; it’s another woman’s baby, and she’s bound by law, right? I don’t know, but that’s definitely what mine is when this scenario was introduced to me. Okay, enough about abortion for now, I’ll touch-on it more in another post. A similar argument, though, can be made for something like rape, which most people I think would agree, is also wrong. For most people, as soon as sex no longer becomes consensual, it is considered rape. However, by law, California would not convict a rapist if a female had initially consented to sex but changed her mind later the same night. Her changing her mind after initially consenting is very similar to my previous example where the surrogate mother changed her mind after signing her legal contract. What’s the difference between these two scenarios, moral relativists?

Objectivity is greater than morality

Our laws: they’re objective. Sure, people can make excuses all they want, but a murderer is going to be convicted regardless of his intentions. Our definitions for things may be subject to editing and clarification, but for the most part, they’re still objective: a cat is not a dog. Colors: objective. Empirical research findings: objective (can be biased, though the numbers remain objective given the methodology). Laws of physics: objective; the human hearing range and the frequency of visible light: objective.

As soon as emotions or passions come into play, though, what were once considered to be objective lines tend to blur. According to our society: Gender: subjective; Women’s rights: subjective; God’s existence: subjective; morals: subjective. Ironically, these emotions empowering humans to do what they want in the universe are objectively nothing more than chemical reactions within their brains as a result of external environmental stimuli… yet we trust them with our judgements between right and wrong?

More reading/ Other arguments:

- Is Morality Objective? (Philosophy Now)

- Islam and Objective Morality

- Atheism and Morality (from a Muslim Perspective)

- True Morality (from an Orthodox Jew)

- Objectives to Objective Morality (Article)

- 6 Reasons why Objective Morality is Nonsense (Blog Post)

- The Catholic Church on Morality

- Objective Morality is Indicative of God’s Existence